by Basak Kus*

“It is China, more than any other place that has served as the ‘other’ for the modern West’s stories about itself, from Smith and Malthus to Marx and Weber,” wrote historian Kenneth Pomeranz in his book The Great Divergence. The historical origins of the East–West divide—why Europe and China’s developmental trajectories diverged so profoundly in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries— has long occupied the social sciences. Much has been written about differences in institutions, culture, and technology, with some arguing that China’s lag was inevitable, while others, like Pomeranz, suggest that it was more contingent. Whatever the explanation for the past, today’s developments suggest a reversal: China is no longer the foil against which the West defines its own modernity but is now at the center of reshaping global futures. Perhaps nowhere is this more evident than in the country’s surge of global investment in green manufacturing.

Xiaokang (Harold) Xue and Mathias Larsen have just released new data on Chinese foreign investment in clean tech manufacturing published by the Net Zero Industrial Policy Lab at Johns Hopkins University, co-directed by Apratim (Tim) Sahay and Bentley Allan. Let me first make clear just how commendable Xue and Larsen’s effort is: the authors devoted more than a year to carefully tracking Chinese companies’ foreign investments in clean technology manufacturing. Until now, the available data came from a patchwork of sources. Larsen and Xue’s dataset is the first truly comprehensive one.

Before turning to the broader implications, here are some of the key trends the report lays out:

- Chinese firms have launched an unprecedented wave of overseas investment in green industries, amounting to $227 billion (going possibly up to $250 billion). As the authors note, this rivals the scale of the Marshall Plan in today’s dollars. And just like the Marshall Plan, this surge also comes at a moment of global geopolitical rebalancing.

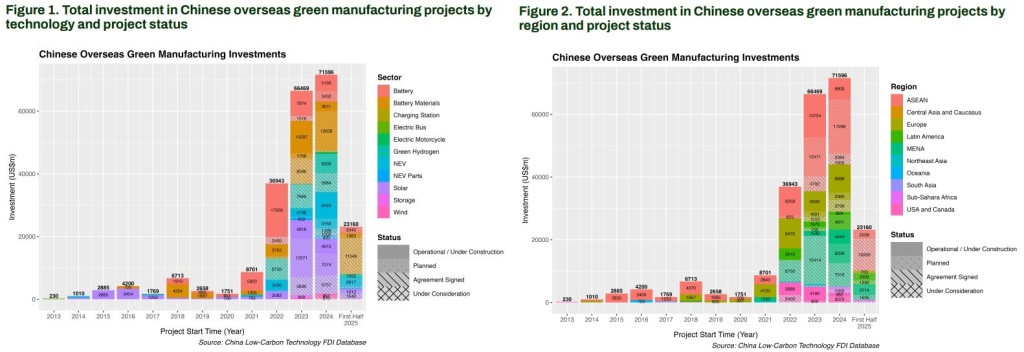

- The investment surge is a recent phenomenon. For years, investment levels had remained modest, but beginning in 2022 the pace shifted dramatically, marking a new phase of rapid expansion.

- Sectorally speaking, China’s outward investment portfolio seems to have broadened. In the pre-COVID period, solar energy was the overwhelming focus. This recent surge came with considerable diversification, however, with Chinese capital pouring into batteries, EVs, wind, and green hydrogen.

- The geography of investment seems to have broadened with this new leap. While ASEAN still remains the primary host region, the Middle East and North Africa have also received a significant degree of investment (over 20 percent of new deals in 2024), and Latin America and Central Asia have emerged as new sites of interest. All in all, Chinese projects now span more than 50 host countries.

- This recent investment surge is not state-driven. This is an important contrast with China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched in 2013. Then, the state had led Chinese firms to build infrastructure corridors across Asia, Africa, Europe, and beyond to expand trade links and connectivity. BRI was dominated by sovereign lending, often in carbon-intensive sectors like coal, steel, and construction. This recent wave, on the other hand, is driven by private companies themselves.

What motivates Chinese firms?

In a recent webinar organized by the Net Zero Lab, the authors, together with Lab’s Co-Director Tim Sahay, highlighted three main objectives.

The first is seeking entry into host-country markets where governments are actively promoting local production of clean technologies while also attempting to protect these industries by putting rules and tariffs. Brazil (Nova Indústria Brasil) is a good example of that. In November 2024, Brazil nearly tripled the import tax on solar modules in response to calls from domestic manufacturers, while also introducing local content requirements that enable developers using a set share of domestically produced equipment to access concessional financing from the national development bank.

The second objective is access to third-party markets. With tariffs blocking direct Chinese exports to the US and Europe, it makes sense for Chinese firms to set up manufacturing in countries that have access to these markets through preferential trade agreements. Morocco, which has free trade agreements with the US and the EU, is an example of this.

Third, as the production scale increases, Chinese companies find themselves needing to secure critical raw materials and processing capacity for clean-tech production. Indonesia’s nickel sector illustrates how host governments can leverage this demand.

Why is this all a game changer?

First mover advantage. China’s green surge represents not just an investment wave but a profound first-mover advantage in the global competition for clean industry. By deploying capital early, Chinese firms are establishing dominance across multiple green industries—solar, batteries, EVs, charging infrastructure, wind, and even hydrogen—not only locking in supply chains but also setting technological benchmarks others must follow before they can catch up.

At the same time, Chinese capital coughing up close to 250 billion into over fifty host countries unsurprisingly gives Beijing political leverage and strategic influence, imprinting Chinese technology and finance into the development models of diverse regions. Much as Britain’s coal and colonies once underpinned its industrial revolution, China’s expansive overseas partnerships now serve as anchors for its industrial leadership in the green age. Most importantly, by branding itself as the leader of the green transition, China is not only building hardware but also defining the new narrative of modernity.

Growth and Decarbonization. What China’s recent trajectory suggests is that the pursuit of growth itself can become a driver of decarbonization. That is, after all, what China has done: cast green transition as an engine of growth and global competitiveness. In this framing, growth is not necessarily at odds with greening, and greening is not merely a constraint or a cost imposed on economic growth; it is—at least in China’s case—actively harnessed as the next frontier of accumulation, competitiveness, and geopolitical leverage. Again, for this is worth emphasizing: this amounts to positioning decarbonization not as a drag but as the very foundation of the next industrial revolution—an approach that, if sustained, would allow China to enjoy the payoffs of first-mover advantages while Europe and especially the US continue to debate how to balance climate policy with economic performance.

Polytunity

In “Turning Polycrisis into Polytunity,” the formidable political economist and China scholar Yuen Yuen Ang reframes disruption not as paralysis, but as a chance to break from industrial-colonial paradigms (the old templates of how economies develop), to build something new. Ang’s adaptive political economy framework implies that actors don’t need to imitate the West’s institutions or follow linear trajectories. Instead, they can use their existing resources, experiment, innovate, and define new paths appropriate to their contexts. China’s green investment surge looks exactly like this: it is adaptive, innovative and ambitious.

New Questions for a New World

All of this creates a goldmine, intellectually speaking, for comparative political economists, opening up new questions, and offering fresh material to study how states, markets, and firms interact across different national contexts:

Which domestic coalitions (local manufacturers, labor unions, environmental groups, political parties) benefit from or resist Chinese green investments? How do host-country elites balance foreign investment with domestic developmentalist goals? How do variations in governance affect how Chinese FDI is received and regulated? Who within host societies gains jobs, training, or industrial linkages from Chinese green investments, and who is left out? How do local political dynamics influence whether communities view Chinese projects as an opportunity/developmental or as a threat/extractive? Going forward, how will host-country governments navigate between Chinese investment incentives and Western political and economic demands and relationships?

So many fascinating developments to watch as the global landscape of green industrial investment takes shape.

Read the report here: “China’s Green Leap Outward: The rapid scale-up of overseas Chinese clean-tech manufacturing investments”

————-

* Basak Kus is Professor of Government at Wesleyan University. She teaches and writes about the interplay between the state, capitalism, and democracy. Professor Kus is the author of Disembedded: Regulation, Crisis, and Democracy in the Age of Finance (Oxford UP, 2024) and is one of the editors of Socio-Economic Review.

***

Since you find value in the content and resources shared by the ES/PE community, please consider making a contribution to help sustain our work. Your support is vital to maintaining our independence and carrying forward our mission. Intellectual and civic solidarity matters now more than ever. Every contribution makes a meaningful difference and helps ensure the continuation of accessible scholarship and useful information. Donate securely now via this PayPal link. Thank you!

Discover more from Economic Sociology & Political Economy

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

Environmental Policy is Social Policy – Social Policy is Environmental Policy

Isidor Wallimann, Editor

Click to access ENVIRONMENTAL-POLICY-IS-SOCIAL-POLICY-SOCIAL-POLICY-IS-ENVIRONMENTAL-POLICY-Book-pdf-Springer-2013.pdf

Isidor Wallimann, Ph.D.

Visiting Research Professor, Maxwell School, Syracuse University

http://www.maxwell.syr.edu/faculty.aspx?id=36507226572

https://sustainabilitypolicy.com/

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing reality and thoughtful analysis.

Just recalled: “If you think the economy is more important than the environment, try holding your breath while counting your money.” – Guy McPherson

https://economicsociology.org/2014/08/20/if-you-think-the-economy-is-more-important-than-the-environment-try-holding-your-breath-while-counting-your-money/

LikeLike