David Graeber’s death shocked and saddened so many around the world… The bundles of emotions, memories and appreciation are being reflected in the incessant stream of obituaries and tributes. Links to a handful of them are collected here.

Bruno Latour : “What David Graeber wrote and did had an enormous effect in empowering his readers, and more generally a whole audience of stakeholders, precisely because he was providing an alternative version of the economy in which we are imprisoned. In that sense, one can say that David Graeber was an optimist. However, his death does not make us optimistic at all: it is a shock for all those who hoped that his work would give a way out of the fiction that the economy is.Fragments of an Anarchist Anthropology Bullshit Jobs: A Theory When asked, what is the effect of David Graeber on his own thinking, Latour replied: “A legacy is “diseconomization.” He shows that the topic of production, which obsesses Marxism as much as Liberalism, is a fiction. What is tragic about David Graeber’s death is that few are working to get us out of the economy as a fiction, to get rid of the economy as a principle of analysis of the social world. Economic notions do not grasp the violence of the social world.” (Thanks to Vassily Pigounides for the translation )

Michael Hardt : “One aspect of David’s writing that I greatly admire is the way it combines serious academic research with popular and accessible – and often genuinely humorous – writing. This combination of research and writing styles is, indeed, another facet of his figure as a scholar-activist. “

Paul Mason : “Debt: The First 5000 Years taught a generation of activists that debt is a form of exploitation and repression; and that the progressive outcome of a class struggle over debt is its cancellation. Alongside the analysis of debt itself, Graeber developed the concept of an “everyday communism”, observable in clan-based societies but underpinning all human endeavours based on cooperation. Though under-developed in the book, the idea found an immediate resonance among the networked anti-capitalist activists who had been occupying the squares of major cities, determined to break with the gradualism and timidity of the official left.

Nathan J. Robinson : “Graeber noticed things. Everyone notices a few things here and there, but David Graeber noticed things other people did not. This was partly because he was an anthropologist, trained to shed presumptions about how human societies work and figure out how they actually work, to see people both through their own eyes and through the eyes of others. It was also, however, because he was an anarchist, instinctively inclined to reject the existing order of things and think for himself about what could and could not be justified. But Graeber did not simply see ; he was a committed activist, participant as well as observer, who turned his intelligence to practical questions about how to make people more free to enjoy the brief, wondrous gift of getting to be alive. “

Jerome Roos : “Graeber’s popularity on the left lay in his capacity to communicate complex ideas to a wide audience, combining engaging prose with disarming humour… He revitalised old concepts such as class and revolution, but in a way that gave readers the feeling they had encountered something new and exhilarating. Characteristically generous, Graeber spent his life fighting for a freer, more joyous and egalitarian world. “

Marshall Sahlins : “David was the most creative student I ever had, constantly turning the conventional anthropological wisdom inside out, often to show how ostensibly dominated peoples, by their own means, subverted the states, kings, and other coercive institutions afflicting them to create self-governing enclaves of community. “

Steve Keen : “He was fundamentally funny, and looked on the world with a sense of bemusement, and all the while, incisive insight. He was intrinsically an anthropologist, in that he was capable of living amongst people and seeing their customs more clearly than they could themselves, while all the while celebrating those aspects, the good and the bad, because they were his people as well. “

Jeff Maskovsky: “Many have coined phrases—activist anthropology, public anthropology, engaged anthropology, and militant anthropology, to name a few—to repackage disciplinary knowledge in more media-savvy, morally righteous, publicly consumable, and grassroots-oriented directions. Yet proponents of an “engaged” stance are often reluctant to name explicitly or to flesh out in any detail the political ideologies or philosophies that influence them. Graeber had no such hesitation. His unabashed promotion of an anarchist perspective is more in line, in fact, with the ways that proponents of Marxist, feminist, antiracist, decolonial, and queer anthropology established their political and intellectual bona fides than it is with any “engaged” approach. And, like these more explicitly political approaches, David’s anarchist stance advanced political debates inside and outside of the academy, energized a new generation of politically motivated young scholars, and pushed all of us to elaborate more clearly what we think the relationship between scholarship and politics should be. “

Andrew Ross : “David’s contribution to the theory and practice of Occupy’s conduct and tactics was much more profound and formative for the movement… More than anyone, David helped to revive and push into public consciousness the idea that debts should be wiped clean in a single act of abolitionary justice. It will be his greatest legacy if we can see that day come to pass. “

Brett Scott : “David was a master of a style of anthropology that opens your eyes to the fact that the pallette of economic options is far wider than you might think. While conservative econ departments attempt to naturalise the mentality that accompanies capitalist monetary exchange, economic anthropology – at its best – is like a rebel holdout in our collective subconscious, keeping alive knowledge of other ways of being… He told me [once] how tough it was trying to help out all the groups [calling for debt cancellation] that needed support, but he nevertheless kept at it. This is why David was an anthropological hero to me, because he explicitly politicised and lived his anthropological knowledge. He was acutely aware of how societies bulldozed by colonialism often had – and have – entirely different customs to apportion labour and energy, and was well-versed in the ambiguities of those customs. He believed, though, in our ability to rework this knowledge to challenge the oppressive structures of finance around us. “

Nicholas Mirzoeff : “David was motivated by twin pillars, the radical capacities of the imagination and the need to place care at the center of any community… Reading David’s writing is like being in conversation with him: funny, incisive, and insightful at once, whether he’s talking about Batman, debt, direct action, or kingship. Like Stuart Hall, David was “in the university but not of it.” For all the times I heard him speak, I now realize none of them were in a university. “

David Wengrow: “David Graeber died three weeks after we finished writing a book together about human history, which had absorbed us for more than ten years. It will be called The Dawn of Everything , because he wanted that… It all started as a game really, an escape from our more “serious” responsibilities. Our only rule was no rules: no deadlines, no funding applications. Just a free space to ask questions and seek answers. “

Matthew Zeitlin : “Graeber was a link not just between grassroots movements and the academic world, but between generations of leftist social movements. He was a veteran of the anti-globalization protests in the 1990s who helped start Occupy, one of the facilitators of a debtor movement that would influence the policy agendas of Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders… The question Debt sought to ask was one that seemed natural in the wake of a debt crisis that would claim millions of homes and thrust much of the industrialized world into first a sharp economic crisis, then a self-destructive series of austerity measures designed to stem the tide of sovereign debt. ”

Debbie Bookchin : “Then there was his intellectual generosity. He seemed to project his own brilliance onto others, taking the latent kernel of an idea unrecognized by a speaker and following its logic, then weaving it together with his own knowledge of history, anthropology, and political theory until he had spun a beautiful synthesis, a comprehensive analysis of the subject at hand, for which he was always inclined to give the original speaker credit. “

Benjamin Balthaser: “David Graeber’s intellectual legacy is enormous and wide-ranging, but his recent writings on antisemitism deeply moved me. He knew that antisemitism was far from dead — and he also knew that only a democratic left could stop it. “

My own tribute : “Graeber urged us to reject a narrow and deceptive economism, ask fundamental questions about what human beings are or could be like, and act morally… Graeber lived the coupling of theory and praxis… His iconoclastic research and writing have not just educated and inspired so many, but also paved the way to innovative approaches towards political activism and scientific investigation. “

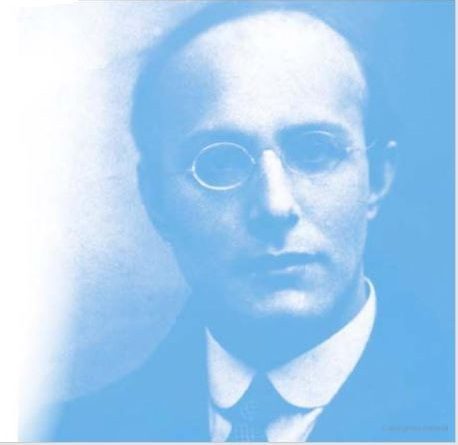

David Graeber, Occupy Democracy on Parliament Square, London, May 1, 2015 ***Economic Sociology and Political Economy community Facebook / Twitter / LinkedIn / Whatsapp / Instagram / Tumblr / Telegram

[…] 59, died suddenly of necrotizing pancreatitis, prompting a shocked outpouring of tributes from scholars, activists and friends around the […]

[…] 59, died suddenly of necrotizing pancreatitis, prompting a shocked outpouring of tributes from scholars, activists and friends around the […]

[…] subitement d’une pancréatite nécrosante, provoquant un choc effusion d’hommages de savants, militants et amis du monde […]

[…] Graeber, aniden öldü nekrotizan pankreatit, şoka neden olan haraçların dökülmesi itibaren bilim adamları, aktivistler ve dünyadaki […]

[…] 59, died suddenly of necrotizing pancreatitis, prompting a shocked outpouring of tributes from scholars, activists and friends around the […]