by Jongchul Kim*

In a given era, social scientists often share a common philosophical perspective, whether overtly or implicitly, despite studying different subjects. So what if the prevailing perspective among mainstream economists proves problematic, preventing them from providing a comprehensive understanding of the capitalist financial system?

In modern Western philosophy, conventional economics is built upon two central concepts: person and property. Surprisingly, there is no academic exploration of how these concepts form the essence of modern money. This absence of theoretical inquiry limits our comprehensive understanding of the true nature of modern money. For instance, the credit theory of money, gaining popularity among heterodox economists, argues that money is credit, representing creditor-debtor relations. Unfortunately, this theory overlooks the distinct nature of capitalist creditor-debtor relations, which differ from their pre-modern form. While creditor-debtor relations have existed for millennia, their prevalence in modern times is unprecedented. What factors have contributed to their widespread occurrence? How do they differ from pre-capitalist forms? My book Modern Money and the Rise and Fall of Capitalist Finance: The Institutionalization of Trusts, Personae and Indebtedness asserts that modern money goes beyond mere creditor-debtor relations. I argue that modern money emerges as a combination of creditor-debtor relations with three personae—the modern state, business corporations, and individualism—and a combination of creditor-debtor relations with property.

These combinations are referred to as a trust. Legal textbooks provide two definitions of a trust. The first definition states that a trust is a double-ownership that makes it possible for two exclusive ownership claims to exist simultaneously over the same asset—legal ownership claimed by trustees and equitable ownership claimed by beneficiaries. The second definition describes a trust as a hybrid between property and debt. The primary purpose of a trust is for the owner to enjoy privileged property rights while avoiding the legal responsibilities attached to those rights. The owner achieves this by transferring legal ownership of the property to trustees while retaining equitable ownership, thus continuing to benefit from ownership.

Trust is largely absent from the classical writings of Karl Marx and Max Weber on the origin and nature of capitalism. However, Frederic Maitland and R.S. Neale presented compelling arguments highlighting the central role of trusts in both the genesis and nature of capitalism. Maitland argued that the transition from feudalism to capitalism was not a shift “from status to contract” but rather “from contract to trusts.” According to him, understanding the essence of capitalism required acknowledging a peculiar form of ownership and collectivism represented by the trust. Maitland identifies the far-reaching effects of the trust on the economy and politics, including the establishment of limited liability joint-stock arrangements and the concept of trusteeship within an imperialist framework. Neale also criticizes the classical theoretical account of the transition from feudalism to capitalism, arguing that it overemphasizes the role of market forces and the bourgeoisie. He demonstrates that the landowning class and its ideology, particularly the trust, provided the essential legal and institutional framework that facilitated the development of industrial capitalism in England, with the bourgeoisie largely adopting trusts without significant alterations. While Maitland and Neale underscored the importance of trusts in the emergence of capitalism, their arguments relied more on intuition than rigorous analysis. This book aims to bridge this gap by providing a comprehensive analysis of the three capitalist institutions: modern money, limited liability joint-stock corporations, and modern nation-states. Through this analysis, this book presents a new theory of capitalism that characterizes its nature as a trust.

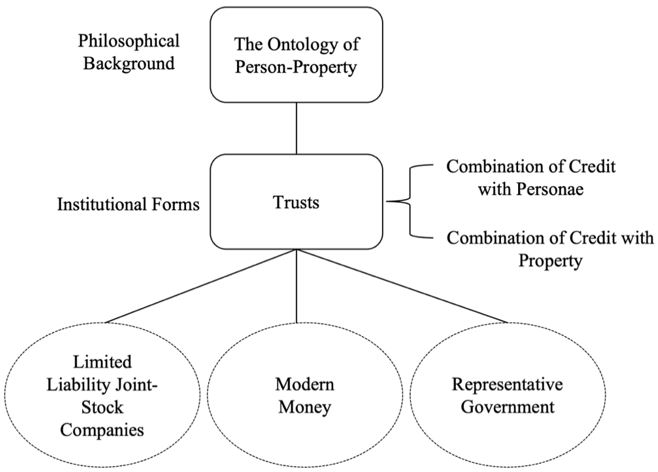

This figure outlines the main concepts discussed in the book. The ontology of person-property forms the philosophical background of trusts, which in turn encompass the three capitalist institutions.

What insights and benefits can we gain from characterizing the three capitalist institutions — money, corporations, and nation-states — as trusts?

First, it provides a compelling explanation for why modern banking originated in England rather than continental Europe. The concept of trust, deeply embedded in English law, distinguishes it from the Roman law tradition prevalent on the continent. Continental Europe has strictly separated property and debt, considering any blending or hybridization of these rights as criminal. Consequently, any attempt to combine property and debt, such as lending demand deposits to third parties in the name of depositaries, was long viewed as embezzlement. In contrast, England, influenced to a lesser extent by Roman law, did not prohibit such mixing. In this favorable legal environment, London’s goldsmith-bankers pioneered the creation of modern bank money in the latter half of the seventeenth century.

Second, it enhances our understanding of the nature of modern money. The ongoing discourse on the nature of bank money has primarily revolved around exploring the nature of demand deposits, since modern banks generate money by creating such deposits in their borrowers’ bank accounts. Ever since the House of Lords declared in the landmark British case of Foley v. Hill and Others in 1848 that demand deposits held with banks constituted loans granted to the bankers, laws have regarded these deposits as the banks’ debts owed to their depositors. Financial theories, including post-Keynesian economics, have subscribed to this prevailing view. However, this prevailing view is misguided because it captures only one aspect, overlooking the hybrid nature of modern bank money, which is both debt and property.

Third, it improves our understanding of the causes of financial crises. The prevailing perspective falls short in comprehending the origins of these crises, leading to misattributions to benign factors. For example, post-Keynesian economists incorrectly identify uncertainty as the main source of these crises, overlooking the significant role that uncertainty plays in fostering creativity and diversity throughout human civilizations. This book demonstrates that the hybrid nature of modern money itself is the root cause of financial crises.

Fourth, it unveils the unique characteristics of capitalist creditor-debtor relations that set them apart from their pre-modern counterparts. While creditor-debtor relationships have existed for centuries, their unparalleled prevalence in the modern era is unprecedented. At the heart of this widespread phenomenon lies the crucial role played by trusts, which relegate collective entities such as the state and business corporations to the position of debtors, who are subject to the whims of their affluent constituents. Without trust, the capitalist creditor-debtor relationship would cease to exist. As social beings, humans are inherently interconnected with their communities, as survival becomes arduous without them. Just as Friedrich Nietzsche criticized the absurd notion of an individual indebted to the community, the idea that the community itself is indebted to its members is equally flawed. This peculiarity of capitalist creditor-debtor relations, where a community assumes such a role, raises profound ontological doubts and skepticism about the prevailing structure of our political systems.

Fifth, it enables a moral critique of capitalist creditor-debtor relations. As discussed earlier, trusts have been established to grant property owners exclusive rights while avoiding the associated legal obligations. Similarly, capitalist financial innovations like lending demand deposits, repurchase agreements, and money market fund shares have been devised to strengthen property rights while sidestepping their corresponding legal responsibilities. This inherent asymmetry between rights and responsibilities in capitalist financial innovations undermines fairness and justice at their core. It disrupts the delicate balance required for a harmonious social order, violating principles of equity and moral rectitude.

Sixth, it reveals that modern banking and finance play a central role in perpetuating inequality. Through the mechanisms of money creation in modern banking, bankers and their clients gain increased purchasing power, allowing them to obtain goods and services produced by other members of society without cost. This results in a transfer of wealth and income from the wider population to this privileged few. This wealth transfer triggers “inflation,” an informal tax payment that the entire society pays to financiers and their clients. Not only do they accumulate wealth through business ventures in which they invest newly created wealth strategically at low cost, their assets value rises as inflation occurs. We can imagine this wealth transfer occurring internationally as long as the US dollar is the world’s reserve currency and the Federal Reserve acts as the world’s central bank, creating the reserve currency out of thin air.

Seventh, it highlights the crucial role of the coercive power wielded by the modern state in shaping banking and finance. Heterodox economists, including post-Keynesians, acknowledge the state’s power to enforce tax obligations as a decisive factor in modern money development. However, they overlook the inherently coercive nature of the power. Karl Marx, in his Capital I, elucidated the coercive and exploitative characteristics of public debt and modern taxation. According to Marx, public debt creates an idle rentier class that effortlessly accumulates wealth while burdening the government with escalating interest payments, leading to impose excessive taxation on citizens. The coercive and exploitative nature of public debt is most evident in its connection to war, as it serves as a highly efficient mechanism for rapidly extracting war resources on a massive scale. Capitalist banking has thrived due to public debt and imperialist warfare, because it facilitated the efficient transfer of wealth and resources to the military sectors at the expense of the broader society. The nexus between military, banking, and public debt that began in in early modern England remains relevant for shadow banking in twenty-first-century America.

Last but not least, it enables us to grasp the solutions for reforming capitalist banking and finance: abolishing the hybridity of property and debt, while advocating for the use of independent group personality exclusively for the advancement of social welfare.

——————–

* Jongchul Kim is Associate Professor at Sogang University, Seoul, South Korea. He previously held postdoctoral positions at the Columbia University Law School and the Max Planck Institute for the Study of Societies.

***

Feel free to share this post. Enter your email at the top of the page to receive new posts.

Follow Economic Sociology & Political Economy community on

Facebook / Twitter / LinkedIn / Whatsapp / Instagram / Tumblr / Telegram

Insightful analysis of conventional economics and its limitations.